Can there be a Magic Pudding? ... towards an understanding of viable farms

Sam Sawnoff, Bill Barnacle and Bunyip Bluegum from Norman Lindsay’s book The Magic Pudding

Bill Barnacle, Sam Sawnoff and Bunyip Bluegum had a delightful meal, eating as much as possible, for whenever they stopped eating the Puddin’ sang out – “eat away, chew away, munch and bolt and guzzle, Never leave the table till you’re full up to the muzzle.”

This is the written form of my Inaugural Public Lecture, presented in 2005 in Armidale, NSW, Australia.

It represents my attempt to condense my disciplinary learning up to that time in a single document.

My goal in this paper was to examine three points:

To explore what I call the “Magic Puddin’ philosophy” as practised by modern humans - and thereby claim that we – not they – are largely responsible for unsustainable farming today;

To explore what we might mean by sustainability and how we might assess it; and

To make a case for us, for all of us, to learn what comprises a viable farming system.

Link to entire paper (12,500 words).

Link to entire paper (12,500 words). Whilst it might be available in the National Library, I figure it might be more easily accessed by putting in up on this web page.

If you are interested in food and how it might be produced more sustainably, you might like to read what this ordinary scientist has written …

Why is it that most humans take their food for granted?

Throughout history, societies have behaved as if our food supply will last forever - until it doesn’t!

I argue here that it is perilous for us to have a ‘Magic Puddin’ view of food - and of the agriculture, farming and our precious soils which produce it.

An increasing proportion of human societies are living in cities where they are disconnected from the fundamental processes that support viable farming systems.

The gluttony displayed on some reality TV cooking programs in some well-fed parts of the world reinforces my view of the disconnect many have with where their food comes from and how precious it is.

If you are one who eats, I invite you to read about such matters by opening the entire paper or by reading some of these juicy bites of puddin’ below …

From the Introduction: “Worldwide, no other single factor so reveals the commonality, yet so emphasizes the disparities, of the human family as does food. The daily consumption of food is so natural and so necessary as to be an instinctive human act”. (Professor Ivan Head keynote address to the United Nations on World Food Day in 1996)

The Magic Puddin’ philosophy: Can there be a magic pudding to feed this hungry world? Let us fervently hope so! It seems to me that humans, by their behaviour, must believe that there is indeed a magic pudding – that food and fibre will be produced in bountiful quantities indefinitely into the future.

History of Land Degradation: “Now if the mountain’s forests are over exploited, the forests at the foot at the mountains will be destroyed, the swamps will be exhausted, the people’s strength will be used up and the fields will become devoid of crops and full of weeds. Resources will have been squandered. The gentlemen will continuously express shock and regret. Moreover how will it be possible for there to be any happiness?” (Guoyu 400BC)

A little good news: In spite of the degradation referred to above, according to Michael Lipton (Lipton 2004), the past 50 years has been an era of unprecedented poverty reduction across the world. Nevertheless, he stresses the need for high input yield growth on good land if we are to be able to sustain food production across the world. He notes that low input agriculture is not the solution for increasing yields.

Why people are poor:

Urban bias - Lipton claims that the most important class confl ict in the poor countries of the world today is between the rural and the urban classes. Most of the poverty in the world is associated with the rural sector whilst the urban sector ‘contains most of the articulateness, organisation and power’. This has led to inequities in the development of social infrastructure.

Scarce investment - Perhaps Lipton could be talking about Australia today when he writes: Scarce investment, instead of going into water pumps to grow rice, is wasted on urban motorways. Scarce human skills design and administer, not clean village wells and agricultural extension services, but world boxing championships in showpiece stadia. Resource allocations, within the city and the village as well as between them, reflect urban priorities rather than equity or efficiency. (Lipton 1989)

Cheap food - It is in the interests of both the urban employer and the employee that food should be cheap so that workers can afford to eat whilst wages can be kept low. Lipton points out that the entire rural community suffers when food is too cheap.

Government focused on the city - There is nothing wicked or conspiratorial about this … it is only one of many ways in which the city (where most government is) screws the village (where most people are) in poor countries. In tax incidence, in investment allocation, in the provision of incentive, in education and research: everywhere it is government by the city, from the city, for the city. (Lipton 1989)

Rural – urban divide: Thus, it is clear that those who cultivate the land are seen by much of society as of the lowest class, order or rank and are not necessarily land owners. The rural–urban divide is becoming more serious with time. In the more developed countries, only a small minority of the population lives in rural areas. In the less developed countries, there is a rapidly declining percentage of people living in rural areas. Hence, in the future, a smaller proportion of people will have a close connection with the production of food and fibre in rural areas.

The dilemma for agriculture is that the consumer wants food to be ‘as cheap as possible’ whilst the producer wants it to be ‘as expensive as possible.’

Too little food – too many obese people: Today, the widespread adoption of the Magic Puddin’ philosophy by most human societies has resulted in too little food for many hundreds of millions of people. Perversely, it has also resulted in too much food for many! Today we find that about 60% of people in countries such as Australia and the USA are overweight or obese. Those who can afford it, apparently want to eat our fill indefinitely – along with Norman Lindsay’s Bill Barnacle, Sam Sawnoff and Bunyip Bluegum in The Magic Pudding (Lindsay 1987).

The earth does not abide: “Our final appeal, then, is to our fellow scientists, both natural and social, to realise not only the seriousness of the land degradation problem but also its complexity. For social scientists especially it is important to realise that not only do society and polity evolve and change, but so also does the land on which the system of production basically depends; the natural conditions of production are not a “free gift” and the earth does not abide. Natural scientists know this well, but social scientists have been quite remarkably slow to include explanation and amelioration of the waste of the most basic of all resources in their agenda. It is time for a new beginning”. (Blaikie and Brookfield 1987b)

Triple or quadruple bottom line? I would argue that a “politically acceptable” agriculture is not what planet earth wants. Unfortunately, our politicians – being a reflection of most of society – largely hold ‘Magic Puddin’ views of food and fibre production.

Those who do need to be valued by those who donʼt! Some large enterprises today expect up to 3,000 head of cattle or 20,000 head of sheep to be handled by one livestock manager, possibly with additional contract labour available only at certain intensive times. It is little wonder therefore that many choose not to work on the land in Australia. Those who do (produce food and fibre) need to be valued by those who don’t!

Losing the plot: I argue that our consuming society has either ‘lost the plot’ or is so disconnected from it, as to not realise that these realities exist. One piece of evidence that society has ‘lost the plot’ is the huge differential that can exist for water users. Whilst farmers are being charged up to $500 per megalitre for irrigation water, a global drink company pays just $0.03 per megalitre for underground water at Mangrove Mountain, NSW (ABC, 7.30 Report, September 19, 2005) for bottling and selling to the public at prices of more than $1 per litre (or $1 million per megalitre)!

What percentage of your income do you spend on food? Australian household consumption data confirm that a decreasing proportion of household income is now spent on food. In 1963-64, the average Australian household spent 17 percent of income on food whereas by 2003-04, this had decreased to just 10 percent (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2005). Thus, the declining real cost of food to consumers means that the way in which it is produced is becoming of less interest to most people.

It seems that, by its actions, society expects farmers to be price takers. Typically, purchases of food items at the retail end of the supply chain are many times the prices paid to farmers at the farm gate (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Retail and farm-gate prices of selected food items in October, 2005.

This low proportion of the final retail price which is paid to farmers is in spite of the fact that it is the farmers who have to pay most of the costs of production such as owning/renting land, all of the production costs over many months or even years and often the packaging costs prior to sale. In contrast, those who handle the transport, storage, processing, wholesaling and retailing of agricultural products over a period of perhaps one week are typically paid more than 75 percent of the final retail price for their efforts. Commonly, the end result is that farmers are paid insufficient to enable them to care adequately for the land that produces the food.

It is entirely natural that consumers want food to be cheap, safe and convenient – but not if it ‘costs the earth’.

Eventually it is to be hoped, we must arrive at a point in history when the farmer will be paid by the consumer at a rate sufficient to enable him/her to maintain the natural resources from which the food or fibre was derived.

Inequities in social capital: Comparisons of urban and rural Australia commonly suggest that there is substantial disadvantage in rural and regional communities, compared to the cities, in access to education, transport services, the arts and cultural amenities, health services and the Internet.

Australia - living off its capital? Australia is living off its natural capital, especially in the form of mineral resources, and is borrowing substantially to support our ‘quality of life’. The national balance of payments … shows the effects of the rapidly increasing deficit between exports and imports.

It is well known that the ‘terms of trade’ for Australian farmers has continued to decline over recent decades. Whilst it is often claimed that this decline is due to technological advances, one might wonder if it is in fact also related to the marketing power of those who sell products to farmers versus the marketing power of farmers selling their products to the marketing chain?

Farmers are finding it increasingly difficult to pay for the restoration and/or maintenance of the natural capital upon which the farm system depends.

Selling off the farm: In Australia today, partly because of the challenges of farming profitably, it seems that many farmers are more interested in the capital gain that they can obtain during a period of increasing land values rather than gains in productivity that can be earned from the land.

One dairy farm family was recently elevated to the rich list, not from dairying, but after their land near Sydney was re-zoned residential after dairy deregulation.

‘Selling off the farm’ is not a sustainable form of agriculture!

Declining farm numbers: The inexorable declining terms of trade, or the ratio of prices for products sold relative to the costs of inputs, has led to a situation where exiting farming has become a way of life for many. Confirmation of decreasing farm numbers can be seen over the past 25 years, as the number of grain farms in Australia has declined from about 45,000 to 28,000 whilst the average area sown to grain per farm has risen from about 360 to 700 ha.

At the same time, farm debt has been increasing rapidly.

In addition, an increasing proportion of Australian farm families have significant off-farm income – an indication that farming is not a sufficient source of income for many.

Also, recent statistics show that … many young people (15-24 years old) left rural areas for the city. Surely this is not sustainable for rural populations.

Australia – the lucky country: In spite of the problems noted above, in the global stakes, we Australians are well off!

… compared to most other nations, Australians have excellent access to sufficient quality food.

Australia is geologically stable with a great deal of fl at, arable land, wonderful levels of solar radiation, suitable temperatures for growth across most of the continent, is politically stable and the planet needs more fixation of carbon dioxide (through growing plants)!

However, with the recent public pressures to limit the harvesting and supply of irrigation water, it is likely that much of the potential for greater production will remain untapped.

Improving links in the marketing chain: There is a need to improve farm incomes; this may be assisted by getting farmers to participate more actively in the marketing chain. It is instructive to read just how hard this can be, as detailed by P.A. Wright – the first Chancellor of our University – in his book Memories of a Bushwhacker (Wright 1982).

He describes the very real problems encountered in trying to market agricultural products in a way that is advantageous to the producer. He describes how the wool producers who through their “pluck and dogged determination” were able to bring about the selling of wool in their own wool stores in Newcastle rather than shipping it to Sydney for additional cost and potentially lower prices.

But efforts to do so today are being thwarted by the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission which is actively restricting any form of collective marketing which might be seen to be ‘anti-competitive’.

Family farming: The future of family farms has been challenged by the effects of deregulation which is bringing about the need to increase farm size further.

As technology and economics inexorably force change in the farm sector, the survival of the family farm has been brought into question (Lees 1997). As noted by Johnson (1969):

A cynic might even assert that the family farm is an institution which functions to entice farm families to supply batches of labour and capital at sub standard rates of return, in order to supply the general economy with agricultural products at bargain prices.

Lloyd and Malcolm (1997) point out that the family farm responds to the cost-price squeeze with rational responses such as increasing output and revenue and reducing costs wherever possible. They do this by expanding farm size, becoming more intensive or by earning some income from off-farm sources – all of these strategies continue to be employed by family farms today.

In spite of these challenges, the family farm continues to survive because it is an ‘efficient form of business organisation’ capable of great adaptation.

Problems of perception: Problems of perception about farming practices abound in our newspapers and other media. Sensational negative views are often interspersed with a few simplistic solutions. The views expressed in the media are rarely supported by objective facts sourced from persons without an ‘agenda’. For example, media coverage of issues such as land management and climate interactions over recent years include the following newspaper headlines:

Bias floods river diagnosis: irrigators.

Flooded with red tape.

Eating a country bone dry.

Salinity leaves multitude of costs.

Salinity pressures on Murray River worsen.

Trading scheme reduces river salt.

Lucerne could crop salt out of threatened soil.

Undrinkable water and a $100 bn economic disaster: salt is killing our rivers, farms.

Bush support dries up.

Riverland Renaissance.

Thirstiest crop: 21,000 litres of water.

Sowing a disaster.

Fury at scientist’s drought relief call.

Rather than challenge these headlines with the opinions of ‘just another farmer’, perhaps one who may be perceived by a typical urban citizen as one who wants government handouts, let us consider the views of a uniquely qualified farmer (grain, cotton and cattle) and lawyer who is also Chair of Land and Water Australia – Ms Bobbie Brazil. In presenting a keynote address to the conference on Agriculture for the Australian Environment (2002) in Canberra, she said of farmers’ views:

Their experience is generally positive, but threatened

The major threat is the simplistic understanding and reporting that agriculture is destroying the quality of life of all Australians

The majority of farmers are already using desirable practices such as conservation tillage and integrated pest management

There is inadequate recognition of the need for compensation for water rights

There is too much political opportunism and bureaucratic indifference

The ‘dead hand’ of the market results in a ‘parasitic and moribund’ attitude of banks, where the short-term view prevails, resulting in a single bottom line

There is a ‘Great Divide’ – the bush being lampooned as populated by dullards

Consumers take food and fibre for granted

Fashionable prejudice postures as truth and yet

Farmers are hanging in and hoping!

The above claim of negative views held of rural people by their urban cousins is supported by Bourke and Lockie (2001) who wrote that many urban Australians see their rural neighbours as “backward, ‘red necked’, homogeneous, harmonious and conservative”.

Deregulation:

(NB this section if reproduced in full here as what was said then is still of such relevance today - in 2019)

One of the most crucial issues being faced by farmers today is the deregulation of markets, thereby imposing the will of the majority of society which ensures that farmers remain price takers; this results in the market being the principal arbiter of how food and fibre is produced.

As deregulation of the milk market was being imposed, I wrote an article about dairy deregulation titled “The unacceptably high price of drinking cheap milk” (Sydney Morning Herald, August 1, 2001). I asked: where is the sense in a 600 ml bottle of milk costing (in 2000) $1 and bottled water $1.50?

Whilst I have never argued for the retention of different marketing systems in different states of Australia (nor for different railway gauges!), I did argue that this decision was based on inadequate understanding and discussion. At the time, the debate was limited to two arguments – ‘it’s inevitable’ and ‘we’re giving them $1.7 bn in compensation’!

What about the numerous other issues that should have been considered? These include: the social impacts on the coastal communities affected where this form of rain-fed agriculture had hitherto prospered; the move to irrigation areas, increasing demand for our precious water; the consequence of much greater herd sizes making grazing more difficult; potential animal welfare issues; the inefficient nutrient cycling brought about by increased feedlot conditions; and the greater need for transport of milk (which is mostly water) in refrigerated trucks across the nation?

Where was the debate? There wasn’t any.

The consumers were not informed that this would lead to more industrialised production of milk. The winners from this deregulation were the supermarkets – the losers were the farmers, the cows and the environment.

This severing of the link between price and social, environmental and animal welfare consequences was not recognised by almost all of our politicians nor by the media – in spite of my writing about these matters directly to our 650 politicians across Australia, and to the media.

In late 2005, I have been told that at the “CSIRO's Horizons in Livestock Sciences Conference” it was decided that the number one issue for research is now animal welfare! Broader society is becoming very concerned about this issue.

Most humans just don’t get it – our insatiable desire for cheap, safe, perfect food has costs – and animal welfare is just one of them.

Some four years after dairy deregulation, it was interesting to read of some of the trends in a recent Dairy Industry Review published by the Australian Bureau of Agricultural and Resource Economics (ABARE) (Hogan, Shaw et al 2005). The report states, without evidence presented, that the Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) found that the benefits of deregulation accrued to consumers rather than processors and retailers.

The report acknowledges that milk for processing is now trucked in ‘B-double’ trucks from South Australia to Sydney but no estimate of the efficiency of this transport versus production closer to Sydney is provided.

According to Hogan, Shaw et al (2005) Australian dairy farm cash incomes have declined from around $100,000 p.a. (in 2001/2002 just after deregulation) to less than $50,000 p.a. in the two years post deregulation. Over the same period, the rates of return declined from around six percent to negative or zero levels. The report predicts that, in the future, the dairy industry will be faced with: “more intensive dairy farming, greater use of supplementary feeding, increasing herd size and … lower farm gate milk prices”.

The report does not include reference to any measures of the environmental performance of dairy farms since deregulation.

The above criticism of the deregulation of the dairy industry does not mean that Australia has no successful dairy farms left – we do, and they deserve our admiration. And that is the same across the country – many farmers succeeding, at least financially, in spite of the unrelenting pressures put upon them to remain as price takers.

Over recent years, deregulation of farm prices has happened again and again – eggs, sugar, etc. Sugar production decisions in Australia are now “completely commercial” (Anon. 1997). Can food production be sustainable if decisions are “completely commercial”? And deregulation is continuing with recent news making clear that this time, the target is the Australian rice industry.

In Australia, deregulation is being driven by National Competition Policy (NCP), whereby the States have been persuaded by the Federal Government to deregulate industries in the name of ‘competition’ (or suffer severe financial penalties). Over recent years, NCP payments to the States have risen from $369 m in 1997-98 to $751 m in 2003-04 and are expected to reach $781 m in 2005-06.

It is perhaps surprising then, that the chief architect of Australia’s competition policy, Fred Hilmer, expressed in 2003 some regret about the “… social implications (of deregulation). It is “an area in which there should have been more done”, he said (The Australian, August 27, 2003.)

It is clear now – at least to those affected by these decisions – that there have been massive consequences of these policies. It seems to me that they have been dreamed up and implemented by people who do not understand the fundamentals of how food, fibre and energy should be produced sustainably.

Disconnect between price and environment: Let us explore further the disconnection between the economy and the environment which such market conditions bring about.

As Australia is today firmly wedded to a laissez faire (i.e. “let things alone”) economy, we must ask – do we want a laissez faire environment? If we do not want the environment to be treated in such a way, then how should we treat it? Society wants to regulate the environment. If this regulation costs the land manager, who pays for it in a laissez faire economy? This finally results in a disconnection (Figure 8) that seriously affects those who society wants to manage the land sustainably!

Figure 8. Diagram depicting the consequences of laissez faire economic conditions on the environmental effects of food and fibre production systems, their regulation and the disconnection this brings about between market prices and environmental costs.

Land ownership and sustainability: Land ownership is closely connected to sustainable land management as it relates directly to inter-generational succession as well as a land care ethic. Land ownership by the farmer has the advantage that the rewards for correct decision making go to the farmer, and so tend to optimise resource use in farming (Davidson 1981). In contrast, the lack of land tenure experienced in many countries, has led to serious degradation of that land.

The ravages caused by drought and poor returns: The challenges of the Australian climate have been described vividly by Judith Wright in Generations of Men (Wright 1995) and Jill Ker Conway in The Road from Coorain (Conway 1992).

When combined with climatic extremes such as drought, the consequences of generally low economic returns to farmers can show up as infrastructure problems which can bring about the potential for erosion, stock losses and many other forms of degradation. For example, safe supplies of water for livestock is absolutely essential for farming in Australia and yet, many farmers could not afford to make all stock water supplies safe in the recent drought.

In order to highlight the passions that drought can bring about for those faced with it, I would now like to read you a poem written by that dairy farmer I mentioned earlier, (the late) Roger McKnight, who farmed near Victor Harbour, in South Australia.

Whilst it refers to our dry climate, it also highlights the conflicts between urban and rural priorities.

Send ‘er down, Hughie By Roger McKnight (1971)

But we want to go to tennis,

or some other sort of sport,

wails the city-slicking menace

over some old cocky’s snort –

Send ‘er down, Hughie; send ‘er down.

Arr, they want to go to beaches,

petty pleasures they desire,

while me pastures, or me peaches,

or me parsnips all expire –

send ‘er down, Hughie; send ‘er down.

They say that it’ll rain for years,

there’ll be a second Flood.

If all we get is city tears,

I’ll irrigate with blood –

send ‘er down, Hughie, blow ‘em, send ‘er down!

Native vegetation and biodiversity: There are at present, many confusing signals given to land managers. For example, the Federal Native Vegetation Report of 2004 states in part:

The Australian Government notes that the Productivity Commission has found that state native vegetation and biodiversity regulations are imposing significant and unnecessary costs on landholders (Anon. 2004).

There is a great need for more facts about the place of native vegetation in farm landscapes and how it should be managed.

The issue of biodiversity in pasture systems was studied in a national experiment over six sites and four years (Kemp, King et al 2003). It concluded that no site showed an increase in species number with increasing productivity; in fact, greater diversity of species was associated with less yield of herbage for grazing animals. Thus, greater biodiversity within pastures can have a negative production impact for livestock producers. This is not the message commonly being promulgated in the media in Australia.

Sustainability-definitions: Sustainability is concerned with meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It is widely recognised as a journey, not a destination. Some of the elements that need to be attained if sustainable farming is to be realised include:

Farm productivity increases over time in order to combat rising costs

Adverse impacts on the natural resource base are minimised

Toxic residues are minimised

The net social benefit from agriculture is maximised and

Farming systems need to be flexible enough to manage climate and market risks

A broader, more all encompassing definition of sustainable agriculture, has been proposed by Tilman, Cassman et al (2002):

Practices that meet current and future societal needs for food and fibre, for ecosystem services, and for healthy lives, and that do so by maximizing the net benefit to society when all the costs and benefits of the practices are considered.

Why is it so hard to farm sustainably in Australia? Let us consider the many factors which society expects farmers to manage as they attempt to farm sustainably. The major groups of factors can be described as a series of ‘layers’ from climate to economics, shown in Table 1. Added to these are the external factors, of which farmers have little control.

These include: climate variability, water price, water security, water allocations, native fauna and vegetation regulations, chemical residues, environmental flows, fate of nutrients fl owing across landscapes, genetically modified organisms, spray drift across farms and neighbours, profits along the marketing chain, trade barriers, foreign subsidies, exchange rate, town viability, occupational health and safety, availability of skilled labour, etc.

When several of these factors are poorly understood and/or neglected, it is easy to see how a farm might become unsustainable, especially when there are so many external factors beyond the control of farmers.

Table 1. Some of the factors, grouped by ‘layers’, which farmers need to be able to understand and/or manage in order to farm sustainably.

Layer Factors

Climate

Rainfall, temperature, radiation, wind, irrigation water, deep drainage, water-logging

Soil

Soil type, soil depth, soil structure, soil health, soil conductivity, slope, carbon, organic matter, nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, pH, calcium/magnesium ratio, electrical conductivity

Plant

Crop choice, cereal agronomy, rotation legumes, fodder crops, pastures, herbage mass, digestibility

Crop and livestock protection/quality

Insect pests, beneficial insects, plant diseases, weed management, livestock management, product type, product quality

Farm management

Farm variability, cropping rotations, stubble retention, fertilisers, irrigation methods, whole farm water use efficiency, managing salinity, integrated management, best management practices, controlled traffic, precision agriculture, farm safety, farm audits, grazing management

Economic

Prices, costs of production, productivity per hectare, gross margins, size/diversification, debt/equity, net worth

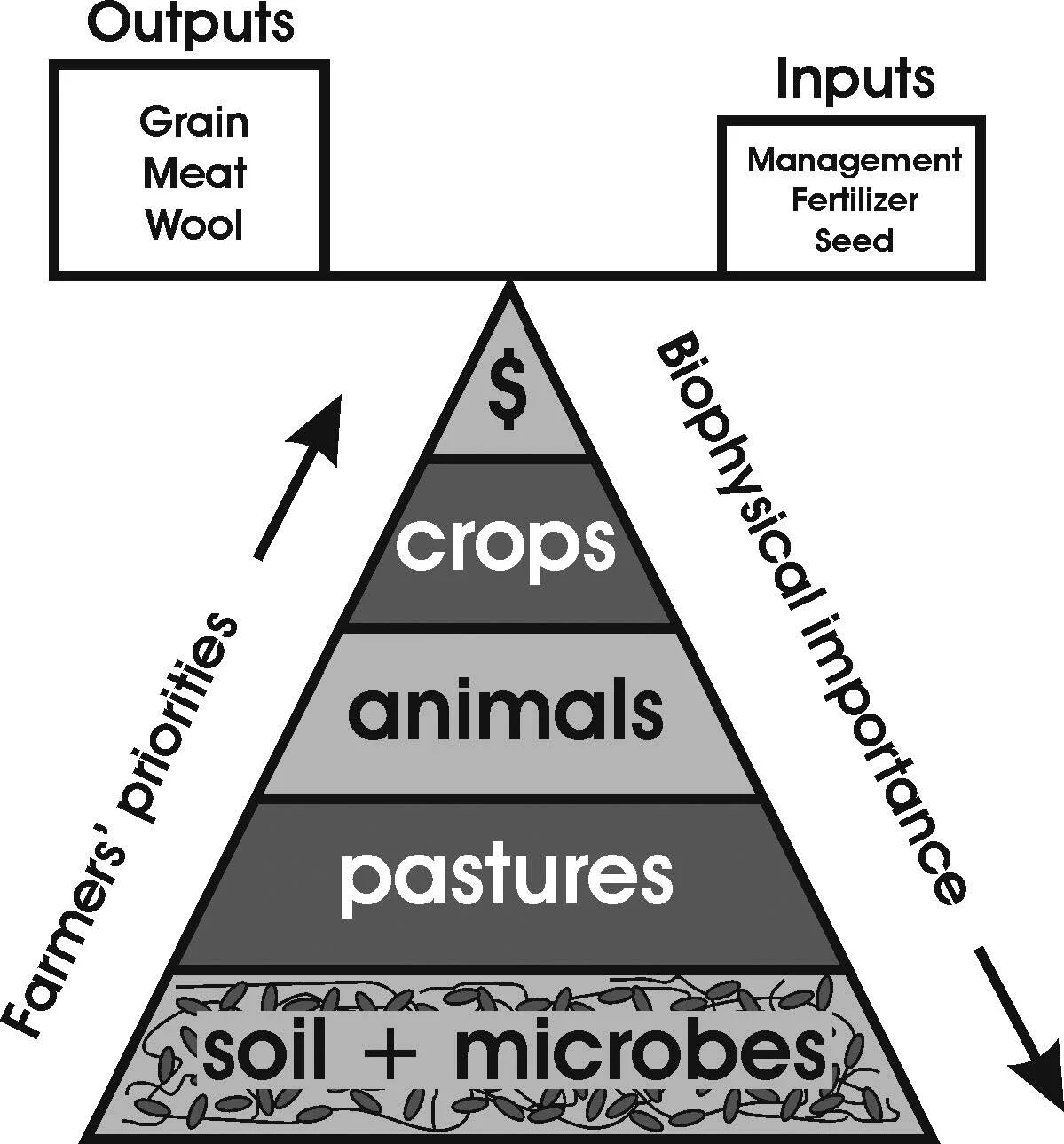

Dependencies between layers of factors contributing to sustainability: The relationship between the functional components of a farm can be viewed as a hierarchy of inter-dependent layers, with the most basic being the soil and its microbial populations (Figure 9). There is a dilemma posed by the priorities of farmers in a laissez faire economy which are focused towards the apex of the triangle whilst the biophysical importance of the layers is greatest towards the base.

Figure 9. Diagram representing hierarchy of layers of sustainability (adapted from Scott 2003).

Of course, sustainability must also include consideration of the time dimension if inter-generational equity is to be achieved.

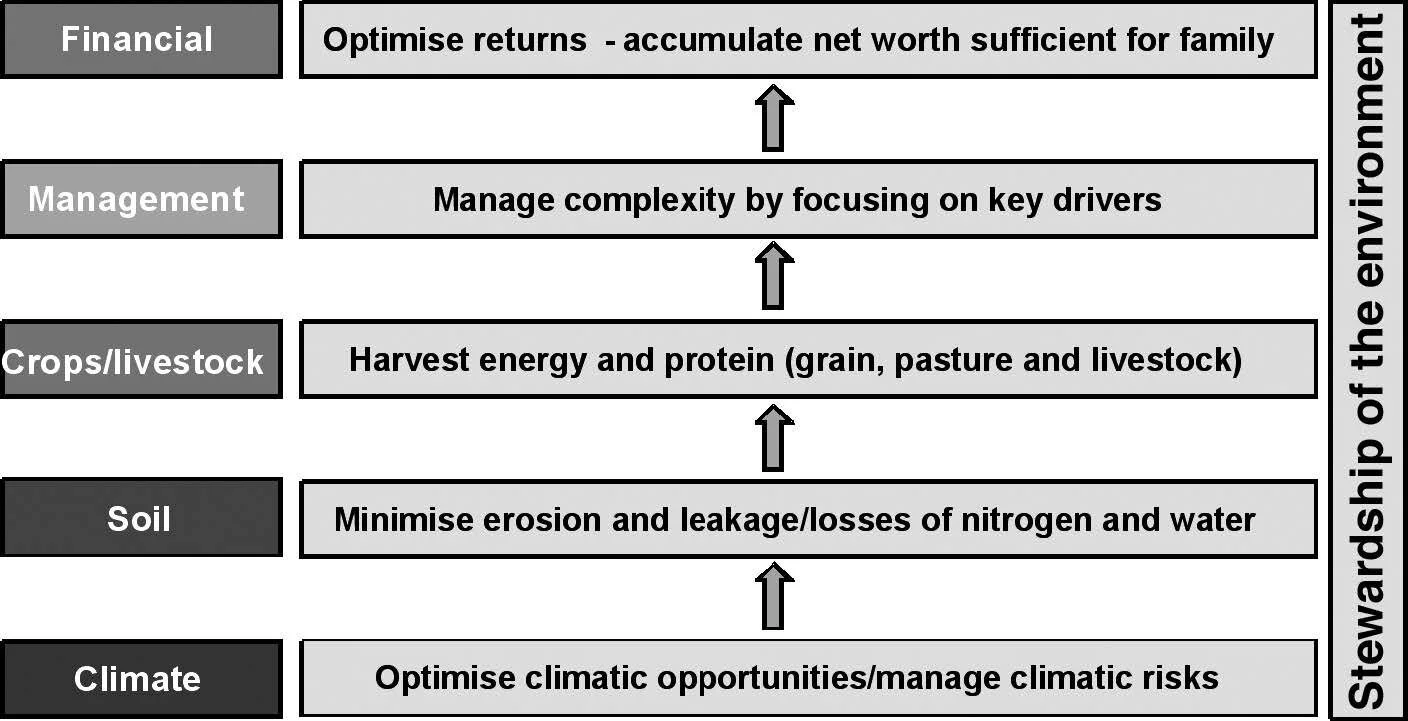

Figure 10 suggests the outcomes which a farmer needs to achieve within and across the layers if their farming enterprise is to be sustainable. These are some of the key indicators that can be used to measure sustainability over time.

Figure 10. Diagram showing simplified dependencies between climate, soil, crop, livestock, management and financial layers of sustainability and the outcomes which need to be achieved in sustainable farming enterprises.

Recent developments and future plans: How can we better manage these complex systems when so many factors and layers interact over lengthy time scales? I suggest that it can be done through:

The creation of ‘fact farms’ where the evidence is credible not only to farmers, but also to researchers, extension workers, regulators and society

Through measurement, monitoring and benchmarking of real farms in relation to ‘fact farms’

Keeping the messages simple through the ‘KISS’ (Keep It Simple, Stupid) principle and

Farmers changing practices after seeing the evidence.

We also need to understand the interactions between different farm components such as cropping and livestock enterprises – and the environment. By striving to understand interactions within functional whole-farms, we can learn how to create more diversified and integrated farming systems which benefit from the synergies between each of the components.

Ultimately, viable diversified and integrated farming systems will help to support the viability of farming communities, thereby leading to positive social and economic outcomes.

What do farmers in our region want?

Table 2. Listing of the major goals of farmers determined at a workshop held in Moree (NSW) in September, 2004 (Scott, unpublished).

Category Goals

Diversification

Mixed farming systems need to be innovative and fl exible

Integration

Match land use with land capability

Satisfy farmers and entire community including consumers

Manage synergies between different enterprises

Environmental

Both catchments and whole farms will be environmentally sustainable.

Farms need to be environmentally sustainable; farmers will be rewarded appropriately for meeting targets

Healthy, living soils and high quality water will support improved crop and livestock yields

Economic

Open market for farm products including free trade among trading partners

High quality produce will result in high prices and will facilitate access to markets

Vertical integration will provide additional benefits to growers and whole farms will be profitable over the long-term

Return of 10 percent p.a. after living expenses (equivalent to $60,000 per family per year)

Social

The Key Performance Indicators used to monitor progress will be standardised, thus assisting communication between researchers and growers

An economically viable and diversified agriculture within the region will enable social support structures (e.g. artistic, cultural and health) to flourish

Farm families will need to work only five days per week and will be able to afford to take four weeks holiday per year

There is a need for a continuing commitment to strategic planning so that a long-term vision over 20-30 years can be regularly reviewed and implemented

What have we been/what are we doing? I have a dream … of measuring whole farm sustainability and profitability over decades. It has to be done. We can no longer afford to pay lip service to sustainability.

We are planning relevant research and adoption activities as well as enhancing education about our farming systems. Wherever appropriate, we are attempting to conduct research and demonstration at a credible scale. We need to do this as there is a considerable gap between what scientists see as valid research trials and what farmers see as evidence of improved farming practices on a credible scale.

For example, we have been investigating whole farm systems as part of the Cicerone Project, just south of Armidale. Others too, such as the Birchip Cropping Group in Victoria’s Mallee region have been exploring farming systems with considerable success (McClelland, Gartmann et al 2004).

Ultimately, viable diversified and integrated farming systems will help to support the viability of farming communities, thereby leading to positive social and economic outcomes.

In conclusion: In striving for more sustainable and profitable farming systems, we ultimately need our farms to have the following characteristics. They should:

be profitable over the long-term

be capable of storing and using as much rainfall as possible

have a range of enterprises well matched to the capability of the land

result in improved soil physical, chemical and biological properties

result in negligible off-site effects

have sufficient diversification to limit risk and

be energy efficient.

If there is no ‘magic pudding’, we all need to work together if we are to survive indefinitely into the future! I hope that you accept that all of us – Sam Sawnoff, Bill Barnacle and Bunyip Bluegum – and me and you – are largely responsible for any unsustainable farming today.

I hope you agree that we need to learn what comprises viable farming systems for our different agro-ecological regions – by investigating the issues of sustainability at a credible scale over a time scale of at least decades – urgently.

We need the facts about sustainable food, fibre and energy production. And the farmers – together with all those who eat – will need to work together to bring about a new deal where the environmental costs of production for all of us, are returned to the land manager to care for his or her land in a sustainable fashion, and in a way that allows those family farmers and their communities to remain financially and socially viable.